Translation by Erika Sibaja

El Eclipse

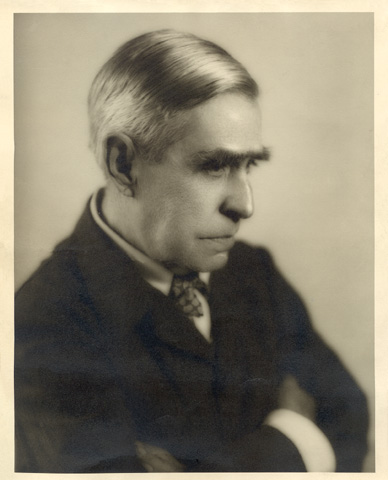

Augusto "Tito" Monterroso

Cuando fray Bartolomé Arrazola se sintió perdido aceptó que ya nada podría salvarlo. La selva poderosa de Guatemala lo había apresado, implacable y definitiva. Ante su ignorancia topográfica se sentó con tranquilidad a esperar la muerte. Quiso morir allí, sin ninguna esperanza, aislado, con el pensamiento fijo en la España distante, particularmente en el convento de los Abrojos, donde Carlos Quinto condescendiera una vez a bajar de su eminencia para decirle que confiaba en el celo religioso de su labor redentora.

Al despertar se encontró rodeado por un grupo de indígenas de rostro impasible que se disponían a sacrificarlo ante un altar, un altar que a Bartolomé le pareció como el lecho en que descansaría, al fin, de sus temores, de su destino, de sí mismo.

Tres años en el país le habían conferido un mediano dominio de las lenguas nativas. Intentó algo. Dijo algunas palabras que fueron comprendidas.

Entonces floreció en él una idea que tuvo por digna de su talento y de su cultura universal y de su arduo conocimiento de Aristóteles. Recordó que para ese día se esperaba un eclipse total de sol. Y dispuso, en lo más íntimo, valerse de aquel conocimiento para engañar a sus opresores y salvar la vida.

-Si me matáis -les dijo- puedo hacer que el sol se oscurezca en su altura.

Los indígenas lo miraron fijamente y Bartolomé sorprendió la incredulidad en sus ojos. Vio que se produjo un pequeño consejo, y esperó confiado, no sin cierto desdén.

Dos horas después el corazón de fray Bartolomé Arrazola chorreaba su sangre vehemente sobre la piedra de los sacrificios (brillante bajo la opaca luz de un sol eclipsado), mientras uno de los indígenas recitaba sin ninguna inflexión de voz, sin prisa, una por una, las infinitas fechas en que se producirían eclipses solares y lunares, que los astrónomos de la comunidad maya habían previsto y anotado en sus códices sin la valiosa ayuda de Aristóteles.

FIN

The Eclipse

Augusto “Tito” Monterroso

When Fray Bartolome Arrazola felt lost accepted that nothing could save him. The mighty jungle of Guatemala had taken him, implacable and definitive.

Given their topographic ignorance, he sat quietly waiting to die. He wanted to die there, without any hope, isolated, with thoughts fixed on the distant Spain, particularly in the Monastery of Abrojos, where Carlos V once time condescended to lose his eminence to say him that he has confidence in his religious zeal of his redemptive work.

When he awoke, he found himself surrounded by a group of indigenous, with impassive face, preparing to sacrifice him on a sacrificial stone, an altar which to Bartolome seemed like the bed where he would rest, at last, of his fears, of his destiny.

Three years in the country had given him moderate native language proficiency. He tried something. He said some words that were understood.

Then blossomed into him an idea of which was worthy of his talent and culture and their hard universal knowledge of Aristotle. He remembered that one of these days was expected a total solar eclipse. And arranges, in the most intimate, make use of that knowledge in order to deceive his oppressors and lifesaving.

-If you kill me, he said to them, I can make the sun go dark at its height.

Natives stared him, and Bartolome surprised disbelief in their eyes. He saw that there was a small council, and he waited confident, not without some disdain.

Two hours after the heart of Fray Bartolome Arrazola dripping its vehement blood on the Stone of Sacrifice (bright under the dim light of an eclipsed sun), while one of the natives recited, without inflection, slowly, one by one, the endless dates in what would occur solar and lunar eclipses, that the astronomers of the Maya community had anticipated and noted down in their codices, without the valuable help of Aristotle.